Historical Context:

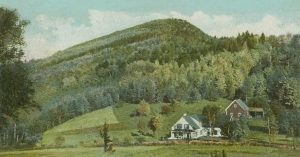

The Gilded Age (late nineteenth century and early twentieth century) witnessed a myriad of economic and cultural shifts. The arrival of the railroad opened the door nation-wide to rapid industrial expansion and, conversely, enabled those with the economic means to escape the very urban blight this growth created. In New Hampshire, the railroad and tourism literature beckoned travelers from New York and Southern New England to “indulge in an anti-modern masquerade of escape” into “a bit of realistic Fairy-land.”[1] The mountain landscapes, articles suggested, provided a calm sanctuary from overstimulation as a result of “the pressures of city work and social responsibilities” burdening white-collar families.[2] Numerous articles and advertisements extolled the region’s idyllic settings and the allure of the sense of “being alone with God.”[3] In response, Grand Hotels multiplied in previously inaccessible mountainous regions: Crawford Notch, Franconia Notch, and Conway, among others. Yet in the shadow of Mount Washington another form of tourism would take root.

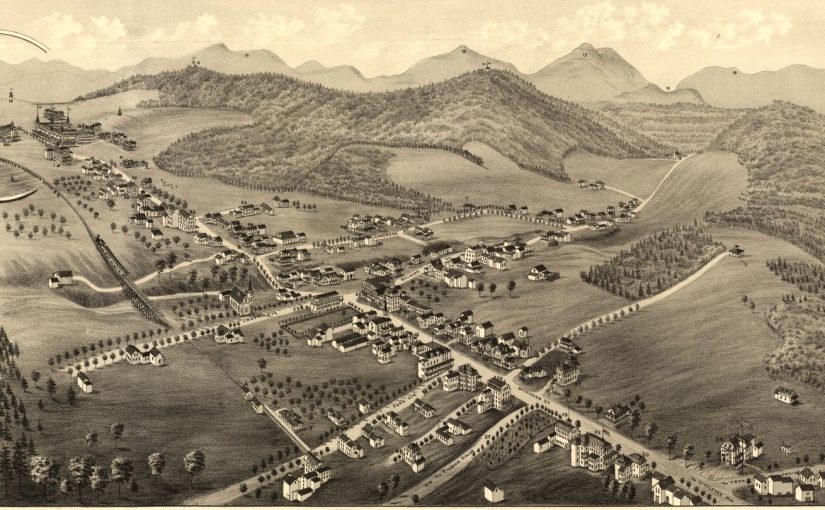

In 1859, Rev. Thomas Starr King published The White Hills, a detailed account of northern New Hampshire’s breathtaking natural beauty. King’s lengthy narrative of the region’s “four valleys,” however, gives short shrift to the town of Bethlehem. He noted that it was “a great pity that Bethlehem [was] not one of the stopping places” for travelers. King praised the town’s commanding panoramic view of Mount Washington but simultaneously disparaged its public houses.[4] What changed? How did Bethlehem emerge as one of the leading health resort communities? What influences people to change their views of place? What can we learn from this exhibit that enables us to reexamine our understanding of health, tourism, and travel today?

The Gilded Ages also saw dramatic changes in medical treatments. The very pressures of urban living that provided economic growth and increased the demand for mountain escapes also led to better health for many. More and more people from the upper middle-class and the elite suffered from nervous exhaustion caused by “overwork.”[5] Physicians prescribed rural breaks of several weeks or months as essential to their patients’ continued good health. More than ten years after Thomas Starr King published his monograph, those afflicted with a variety of diagnosed seasonal disorders were to find relief in Bethlehem’s high altitude and “clean” air. [6]

Linda Upham-Bornstein, Ph.D.

Medical Context

From the 1860s to the 1960s, American medicine expanded and changed dramatically. The Civil War contributed advances in nursing, pharmaceutical manufacturing, hygiene, and the use of hospitals. The development of the “germ theory of disease,” or bacteriology, led to stunning discoveries in the late nineteenth century. Microbes that caused diseases like rabies, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever appeared under the microscope, and vaccines or cures for a few diseases came close behind. Hopes and expectations rose, but not all conditions revealed their secrets. Nonetheless, new public health specialists gained power as governments at all levels sought to contain disease and improve health. The medical profession exerted increasing control over immigrants, people of color, women, and children; some doctors even took social Darwinism literally by contending that certain people were “unfit” to reproduce.

By the early twentieth century, American medicine had grown in sophistication and confidence, and most Americans relied on physicians’ expertise. The gradual uptake of antiseptic procedures vastly improved surgical survival rates. Hospitals also housed laboratory work, academic training, diagnosis, and skilled nursing care. The 100 American hospitals of 1870 became 6,000 by 1920. Asylums for the mentally ill, sanatoriums for tuberculosis patients, and other facilities treated specialized disorders. An upgrade of medical schools in 1910 led to higher levels of preparation for physicians. New physiological understandings, medications, surgical techniques, and medical devices seemed to tumble forth steadily. Recovery from wounds and illness surged in both world wars as compared with previous conflicts. New vaccines and especially antibiotics offered the promise of cure.

Medicine had also become big business by mid-century. The cultural status, financial rewards, specialization, and political power of physicians rose steadily. Large sums of money for research and facilities flowed from philanthropy, academia, and government. Meanwhile, corporations made handsome profits on patented devices and medications. Many Americans obtained health insurance through their work, in an attempt to keep up with rising costs, while Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s sought to help older and lower-income Americans pay for health care. Throughout the hundred years explored in this exhibit, American’s constant quest for health never abated.

Rebecca Noel, Ph.D.

______________________________________________

[1] Blake Harrison and Richard W. Judd, ed., A Landscape History of New England (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011) 146.

[2] Dona Brown, Inventing New England: Regional Tourism in the Nineteenth Century (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995) 79.

[3] Harrison, A Landscape History, 146.

[4] Thomas Starr King, The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscape and Poetry (Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1859) 26.

[5] Brown, Inventing New England, 172.

[6] Gregg Mitman, Breathing Space: How Allergies Shape Our Lives and Landscapes (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007) 10 – 51.