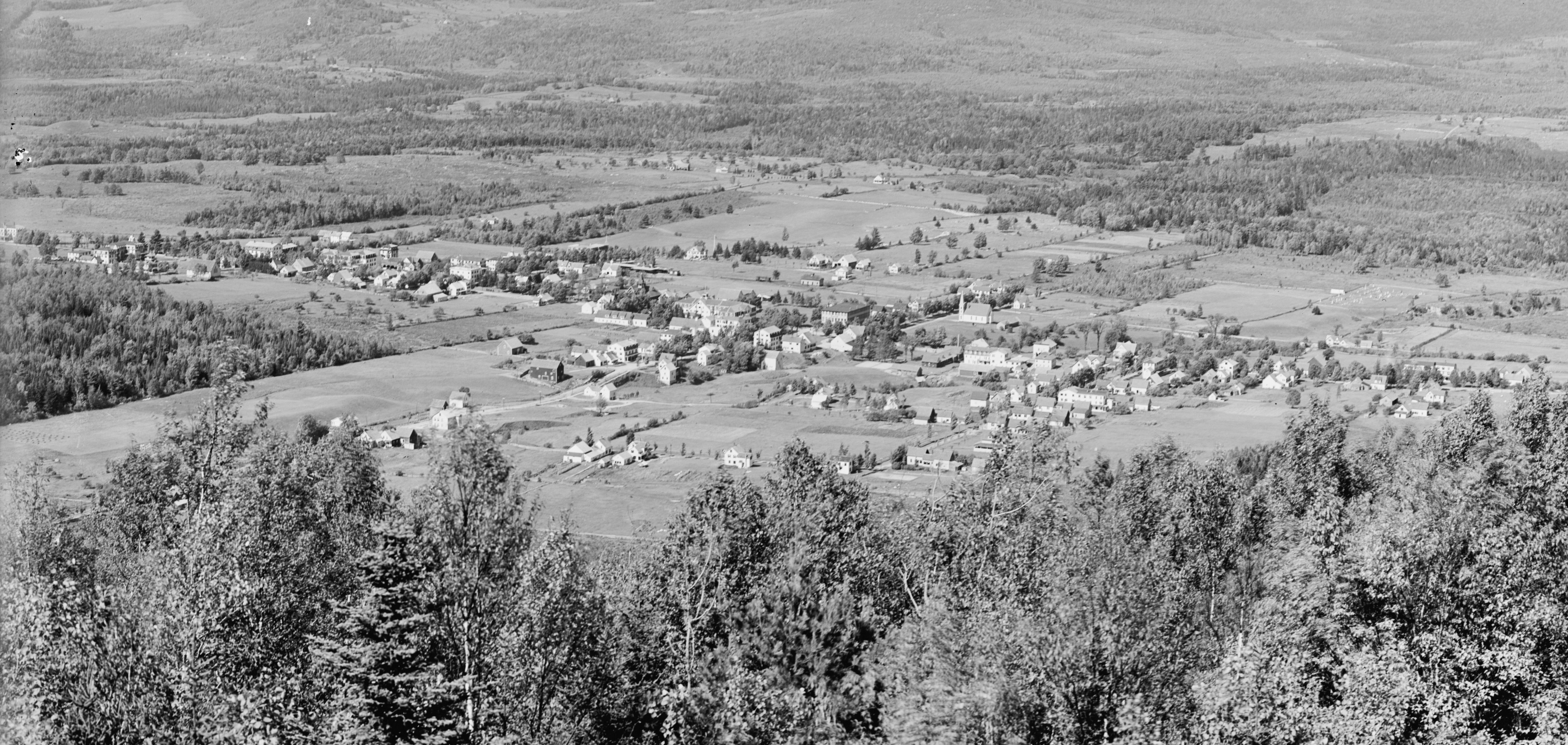

Bethlehem, New Hampshire was a haven for hay fever sufferers, offering relief for a disease that, at the turn of the twentieth century, had no cure. Hotels played a large role in the development of the town, bringing commerce and industry and catering to the guests who arrived each summer. Open from early summer to late fall, they ranged in size. The Sinclair and especially the Maplewood would be considered Grand Hotels, large extravagant sets of buildings that had many, many rooms while the others might have been as small as the Brown Betty Tearoom, which had three guest rooms in it.

Over the years, Bethlehem has boasted somewhere between 30-40 hotels in total, a facet that helped shape the town into a resort community. An 1881 New York Times article describes Bethlehem as having “long rows of hotels and boarding houses”, and “fashionable visitors”.[1] “By the 1880s, the disease had become as prominent a seasonal feature in the society pages of urban newspapers as the cotillions and coaching parades of resort towns.” describes the atmosphere that guests and hotels brought to the area.[2] The 1883 Early History of Bethlehem, New Hampshire, states there were “about thirty hotels” in the town. The Maplewood complex had the capacity to house about 750 guests collectively, with the second-largest being the Sinclair House with accommodations for 300 guests. Turner House and Ranlet’s Hotel each had space for 75 guests, while the Blandin House had room for 30 guests. Simeon Bolles, the author, also listed a series of hotels that could accommodate between 50 and 150 guests; Centennial House, Mt. Washington House, Prospect House, Highland House, Bellvue House, Alpine House, the Uplands, Bethlehem House, Howard House, and Strawberry Hill House. “Hay fever sufferers found in Bethlehem and the surrounding White Mountains physical relief, but also a place whose history affirmed their social identity and shaped their relationship to the natural environment,” writes Gregg Mitman, as guests returned each year, and helped build the White Mountains as a destination point.[3]

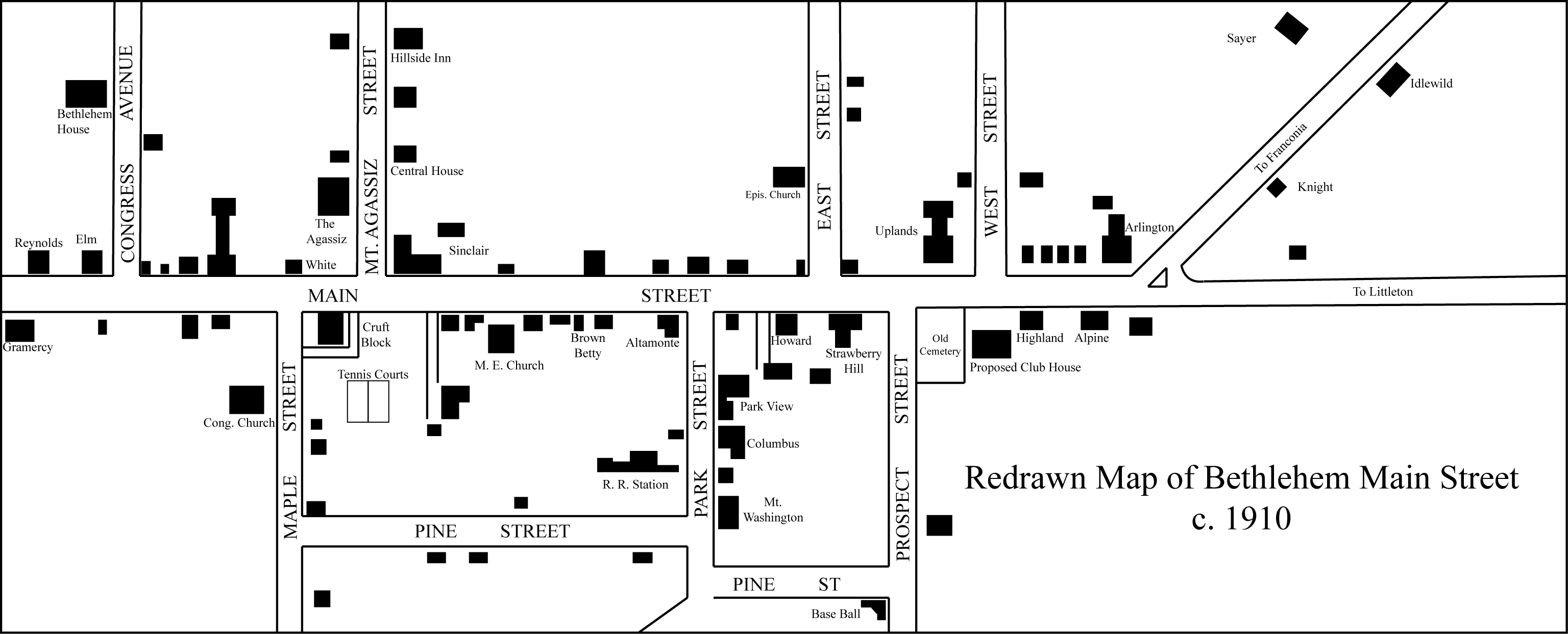

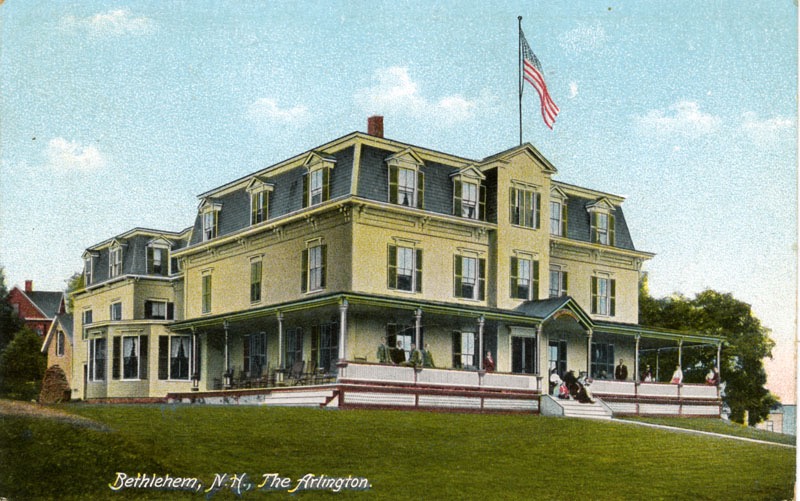

Of these hotels, by 1910 many still remained as depicted in the above map. The Centennial House had become the Arlington, but the Strawberry Hill House, the Howard House and others still sat on Main Street. The Bellvue House was gone in a 1910 map outlining the proposed golf course, which included putting the new Club House on that site between the Cemetery and the Highland House. Karl Abbott, whose family owned the Uplands Terrace, recalls in his memoir that “Father opened his first hotel in 1884”, and purchased the Uplands in 1886.[4] Most of the guests that came to the Uplands in those years were “from New York, Boston, Hartford, New Haven, and Stamford, and another large contingent from Jacksonville and Tampa.”[5] Bethlehem hotels publishing advertisements in the White Mountain Echo boasted livery stables, telephone lines, high-quality food, hot baths, wide piazzas, and amazing views. The Maplewood, which took up one of the largest ads, states: “The Location is beautiful. The Scenery is unsurpassed. The Drives are charming. The Air is marvelous. The Table is first class. The Music is the best. The Casino is commodious. An Ideal Resort For An Ideal Vacation”.[6] A 1914 article writes that they expect many to “motor in” from cities far away, to visit the White Mountains and Bethlehem for the 4th of July.[7] However, visitors were still visiting Bethlehem as can be seen in the “Maplewood Hay Fever Handicapped”, played on the recently constructed Bethlehem Country Club, and the “Maplewood 100”, played in 1921 at Maplewood.[8]

Though the hay fever guests continued to return to Bethlehem to seek clean air until the creation of antihistamines, another form of travelers can be traced to this early twentieth century period. In 1910, Isidore and Sadie Lusher of New York City purchased the Altamonte Hotel, situated on Main Street in Bethlehem, New Hampshire. Though there had to have been Jews visiting town before, some argue this is beginning “of the substantial Jewish presence in Bethlehem”.[9] Hay fever helped shape the town, including in the hotels that were built, the infrastructure created to support the summer visitors, and the conservation that went into shaping the White Mountains as a whole, for tourism in the state. Almost none of these hotel buildings have survived today, having fallen prey to fire, or neglect and were taken down, with the exception of the Maplewood Casino. Though not a complete list, the pictures below correspond to the map, and demonstrate the varied architecture of some of the hotels of Bethlehem as seen in different eras, various styles, shapes, and sizes.

Timeline of Select Hotels with Pictures

Samuel Papps, ’19

Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

[1] “In the White Mountains,” New York Times (New York), August 27, 1881, accessed April 1, 2017, New York Times Digital Archive.

[2] Gregg Mitman, “Hay Fever Holiday: Health, Leisure, and Place in Gilded-Age America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 77, no. 3 (Fall 2003): accessed March 1, 2017, doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2003.0127.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Kimberly A. Jarvis, Franconia Notch and the Women Who Saved It (Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2007), Google Books, 100.

[5] Karl P. Abbott, Open for the Season (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1950), 6.

[6] White Mountain Echo (Bethlehem, NH), August 24, 1895.

[7] “New England’s Summer Paradises Lure Many Jaded City Folk,” New York Times (New York), June 14, 1914, accessed April 11, 2017, New York Times Digital Archive.

[8] “Hay Fever Golfers Out,” New York Times (New York), August 22, 1916, accessed April 11, 2017, New York Times Digital Archive.

[9] Marlena Fuerstman and Edwin Seroussi, “90 Years of BHC,” Bethlehem Hebrew Congregation, January 1, 2017, accessed April 16, 2017, http://www.bethlehemsynagogue.org/news/2014/3/3/bhc-a-brief-history-1920-2010.